The tiny bones of tiny mice, of tiny birds more

fragile than owls, of lizards, confirm what is

already known: that life is always nourished by

life and therefore it endures.

So opens Verónica Zondek ‘s recently released collection of poems ‘Cold Fire’, an epigraph by Gustavo Boldrini taken from ‘Longotoma, Fragmentos de una novela imposible’ (‘Fragments of an impossible novel’), Ediciones Kultrún, 2016.

From Valdiivia in Chile, poet Verónica Zondek is also a translator and editor. She has published a critical edition of the poetry of Nobel Prize winning poet Gabriela Mistral and has translated, into Spanish, the works of Gottfried Benn, Derek Walcott, June Jordan, Anne Carson, Emily Dickinson, Anne Sexton, and Gertrude Stein. And here we have the first translation of her work into English by Katherine Silver, a collection originally published in 2016 as ‘Fuego Frio’ one that doesn’t even appear on her “selected publications” at Wikipedia.

‘Cold Fire’ consists of twenty long poems, in one Verónica Zondek refers to them as “cantos”, all musing on the wind. Burned trees, broken houses, scattered seeds:

And may the windgust

reign supreme and its dangling wings/ that push the

water/ that push the clouds/ that push the rain/ and

erode the stones/ and erode the mount. . .

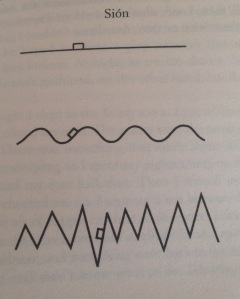

The format of each canto taking on the shape or strength of the wind, sometimes sparse with blank spaces, at other times block text with pauses or line breaks indicated by a dash, occasionally only a few words on a page.

What beast?

What beast is that magnificent windgust that blows

upstream/ that climbs the heavens/ that moves clouds

to collapse over drought?

Meek burns the light through so much fog.

Meek is the cry of the forsaken bones.

Meek is the soul that watches and is flayed.

And on the horizon

A feeble/ wild light/ gallops/ gallops knowingly and

displays its reigns/ and batters/ batters without pity

or pledges.

Now it closes the stars the ancient poem intoned/

and just imagine/ imagine it arriving to soak our

drought/ to sprout it/ and sweet are the tears that

fall from on high/ that pour down/ that fatten the

grass/ an offering. What/ which

That

what beasts and men chew/ of course/ more beasts

than men………… yes………… to continue/ continue

singing/ singing/ s ing ing…………

Because strictly speaking/ they say/ they are only

beasts/ beasts for me enswirled by wind/ by wind

wind/ with its body so fragile/ my body/ and both

so tied to/ so spun into memory/ into thought/ into

love.

The rhythm and cadence lend itself to a reading aloud, words repeated for emphasis, pauses as important as the words themselves, a replication of the wind and the important role it plays in our lives. It would be intriguing to listen to a reading of this work in Spanish and the translation into English thoroughly grabbed my attention, an outdoor reading, in winter, in the Australian bush was an immersive experience. Pauses to listen to the wind, to watch the leaves rustle, the grass bend, the flames of the open fire flicker.

A wind/ a wind that opens the womb/ a wind

that shakes the land/ that sprouts tenderness/ that

squanders heat and swallows/ swallows the pain

of men.

But no/ it doesn’t come/ it doesn’t grope/ it seems to

be only when it kneads life/ when seedlings bloom/

and everything/ everything returns/ returns and

begins again.

Each canto explores a different impact, the dangers of fire being fed by the winds, the devastation of buildings destroyed, light blowing of grasses, you can easily imagine the poet observing and noting the surroundings.

Nature, bones, existence, erosion, impermanence all captured. “Life is always nourished by life and therefore it endures.”

Then:

love/ smile and cry/ sleep/ dream/ kiss with passion

stop/ look/ listen/ stop and let the silver fingers of the

windgust touch you/ and the golden fingers of the

cold fires/ for my letter on the page sleeps while it

waits for the slow roar of awakening/ devouring what

voracious tongues have left behind. Inhaling the tears

of the defeated/ sowing eyes far and wide/ for our duty

is to read/ and reread/ and pay heed/ even if we are

only blood/ and bone. And dream. In this long/ long

and slow bog.

It is our duty to read, and to reread and to pay heed, read slowly, absorb and experience and Verónica Zondek ‘s wonderful new book from World Poetry Books is one you should read (and reread). As Daniel Borzutzky says in the back cover blurb; “Verónica Zondek meditates on the complex intertwinings of our bodies with the social world, the natural world, and death.”