In his “Preface” to ‘L’Assommoir’ Émile Zola claimed the novel “is a work of truth, the first novel about the common people that does not lie and that smells of the common people. And readers should not conclude that the common people as a whole are bad, for my characters are not bad, they are only ignorant and ruined by the conditions of sweated toil and poverty in which they live.”

The protagonist narrator of Zuzana Brabcová’s last novel, ‘Aviaries’, Alžběta is a common person, and is linked inextricably to Émile Zola’s ‘L’Assommoir’;

Underneath the mattress

The trap snapped shut and firmly clamped around my memory. On February 18,1961, my mom had wedged a book underneath my mattress to make sure I’d be sleeping on a flat surface. She forgot about it. Hanging from a long string, a monkey-shaped rattle quivered above me, and I didn’t take my eyes off it for a single moment. They say the blind live in time, not space. If that’s true, I was a blind person back then. All of Grandpa’s clocks ticked away within my veins, and in my left hemisphere, my grandma diced apples from the garden for strudel.

Mom’s friend later took the crib for her own child. She discovered the forgotten book underneath the mattress. It was Zola’s L’Assommoir. (p69)

Whilst Zola’s “project is indebted to the Positivist philosopher’s isolation of three principal determinants on human behavior: heredity, environment, and the historical moment”, Zuzana Brabcová’s novel adds in the influence of literature, literally sleeping on a book, which can determine behavior and in this case fate.

‘Aviaries’ is a collection of fragments, labelled from December 20, 2011 to February 19, 2015, however they are not simply diary entries, there are recollections, newspaper headlines, interior monologues, dreams, excerpts from prose, poetry and psalms (including a passage from C.G. Jung’s essay on the “The Psychological Aspects of the Kore” from 1951 and Oliver Sack’s “An Anthropologist on Mars, 1995). This is a work full of contradictions, that move the reader in contradictory directions, from anger to empathy within a paragraph. It is not unusual for a sentence to spin off in a tangent. All adding to the fragmentary nature of the book;

This frightens me: what if disintegration into prime elements, the fragmentation into particulars, is also true for other phenomena, and reality will churn before my eyes in an incomprehensible muddle? (p78)

Our narrator is from the fringes, being treated for mental illness, recently made redundant with no prospect of reemployment – although she tries – she spends her days emailing her dumpster diving daughter – who is going out with Bob Dylan – and sharing her time and space with a homeless alcoholic who has had “a tumor the size if a lemon removed from his brain”, a soul mate, Melda, who she met in the neurological ward of the local hospital.

“I have no money,” I said to keep the conversation going. “I have no money, no job, no family. Apart from Alice, that is, who’s found lifelong lover in the flap of a discarded wallet in a dumpster, and my sister, Nadia, whose sets all burned down.”

And suddenly, with no warning, Doctor Gnuj quite unexpectedly fixed on me his brown-pink gaze, matching the waiting room, the gaze of a polyp: “Your inner world is like that basement lair of yours. Kick down the doors, file through the bars! Do you even notice the world around you?”

I do. Don’t you worry. I know well enough what the world around me lives for: the season of wine tastings and exhibitions of corpses. (pgs 31-32)

A deeply moving work of social exclusion, it is akin to William Kennedy’s ‘Ironweed’ on magic mushrooms, a melancholic work where we wonder if there is to be any redemption for the narrator as she slips further and further into decline.

Most of the fragments are at the most two pages long and this broken collection of seemingly disparate parts is well suited to exploring a life on the edges, where the kaleidoscopic motes blur the lines between fantasy and reality. As the publisher’s notes say “to testify to what it is like to be alone and lost and indignant in a world that has stopped making sense.”

And suddenly I recall how my mom took me to see a psychologist once, I was twelve or thirteen and maybe ever weirder back then than I am now, I don’t really remember, even memory is just a play of colors and shapes behind eyelids shut in a desire for non-existence. He showed me some pictures, ink blots symmetrical along a vertical axis running through the center of the card. Did it remind me of anything? Was I supposed to let my imagination run wild? What swaddled dimensions, what unknowable universes existed back then, just like today, between my mental images and the words I was forced to use to express them?

Indeed: the infamous Rorschach test.

“A blot,” I told the psychologist when he showed me the first card, but I imagined horse shit on a forest path, which was very strange, given the path was so narrow, no horse could possibly squeeze its way down it.

“Okay, but what does the blot remind you of?”

“A blot.”

“And this picture?”

“A blot. A blot. A blot.”

It reminded me of the noble profile of Old Shatterhand’s face, it reminded me of a human brain and a singed map of Prague, it reminded me of…But why in the world should I tell him that? Just like today, I stubbornly insisted on words quite different to those bursting inside me like bubbles on the water’s surface.

Melda’s lying on a foam mattress and drinking no euro-rotgut but the good Chilean wine he’d given me for my birthday. He drinks it all in one go, being an alcoholic. And me? A blot. Behind the closed eyelids of God knows who. Blots. (p52)

Zuzana Brabcová has taken the three principal determinants on human behavior: heredity, environment, and the historical moment, from Zola’s ‘L’Assommoir’, set the tale in modern day Prague and blended these into an experimental “morass of the bizarre and the grotesque”. At times the protagonist Alžběta is referred to in the third person, others the first, omniscient overlaid with monologue, this approach forcing to reader to recoil, but then to embrace.

‘Aviaries’ was the winner of the Josef Škvorecký Award, a Czech language award in 2016 for the best prose of the year, unfortunately Zuzana Brabcová had died soon after completing this work. A social commentary on the political state in Prague and the ill treatment of socially disadvantaged people, this is a powerful and lingering book.

As Émile Zola says (again) in his Preface to ‘L’Assommoir’; “ I wanted to depict the inexorable downfall of a working-class family in the poisonous atmosphere of our industrial suburbs. Intoxication and idleness lead to a weakening of family ties, to the filth of promiscuity, to the progressive neglect of decent feeling and ultimately to degradation and death. It is simply morality in action.”

Whist Zola has a simple linear narrative arc, a moral story of decline into squalor, Zuzana Brabcová starts us deeply immersed in the mire, the opening fragment at sunset;

December 20, 2011

It arrives around four, five o’clock in the afternoon, hangs around until about seven, and then at night it reigns. It’s been that way for years, I don’t recall it ever having been any different. A day devoted to staying in is the music of a melody nobody has ever played. And when I do have to go out, there’s a bloom coating the people I pass, a frost blurring their features. I can imagine they don’t exist, and in this way I love them. All that exists: just disrupts and mars, as if somebody had graffiti-tagged The Night Watch.

Václav Havel died the day before yesterday. In his sleep, in the morning. So its reign extends beyond the night.

The book starting the in the days after the first President of the Czech Republic’s death. Even the reference to Rembrandt’s ‘The Night Watch’ pervades the opening with darkness, will there be an escape from the gloom?

Brabcová draws on a number of Zola references;

and she looked along the outer boulevards, to the left and to the right, her eyes pausing at either end, filled with a nameless dread, as if, from now on, her life would be lived out within this space, bounded by a slaughterhouse and a hospital. (‘L’Assommoir’ p33)

No, I really can’t complain about where I live. I have a complete range of public facilities nearby: two hospitals, numerous pharmacies, a cemetery, even a crematorium. (‘Aviaries’)

A highlight of my recent reading journey and yet again a great publication from Twisted Spoon Press in Prague. Now I have read Zuzana Brabcová’s final novel I am eagerly awaiting more of her work to appear in English, ‘Rok Perel’ apparently the first Czech novel to deal with lesbian love, set in a psychiatric hospital it deals with an adult woman’s love for a young girl. Her first novel ‘Daleko od stromu’ was published in 1984 in Cologne and Zuzana Brabcová was the first recipient of the Jiří Orten Award in 1987, a prize established to raise the profile of authors whose works had been rejected by the regime. Her work ‘Stropy’ (‘Ceilings’) won the Magnesia Litera in 2013, the title referring to the thing which people hospitalised in psychiatric clinics see most often – a ceiling. All of these blurbs (taken from the Czech Lit website), look most appealing indeed, let’s hope some translators are on the case.

I think it is going to take something special for this book not to remain at the top of my highlights for 2019 and if you enjoy works that push the boundaries, books that examine the fringes, mysterious, grotesque and hallucinatory works then I suggest you order a copy of this post haste.

Copy courtesy of the publisher Twisted Spoon Press.

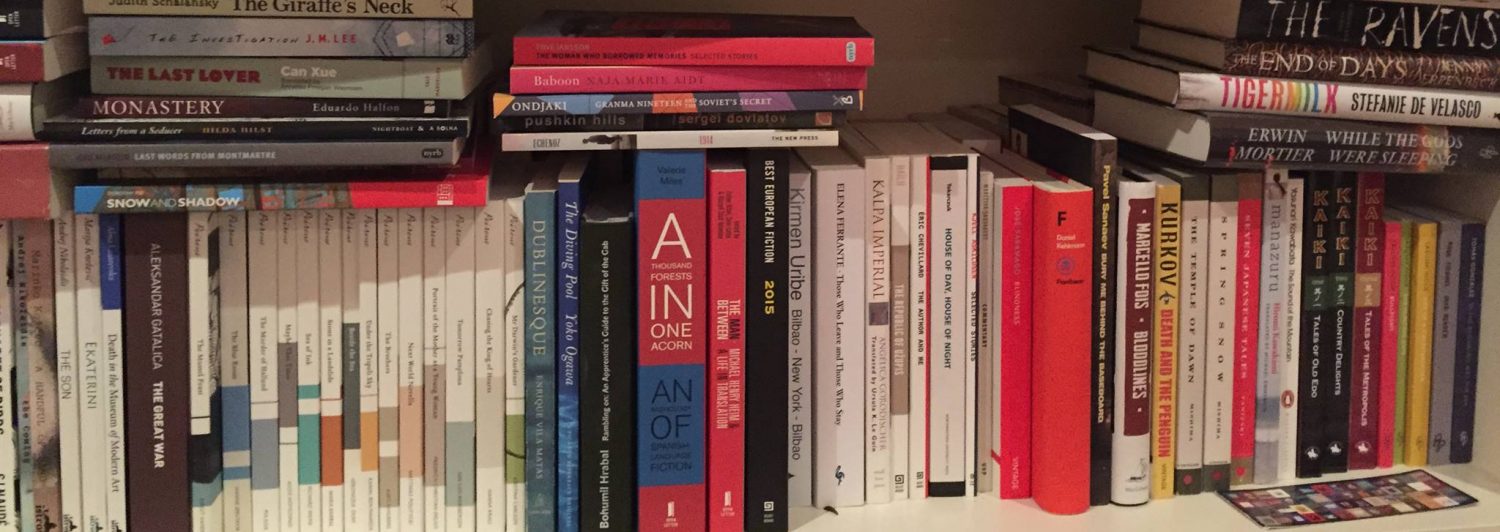

Down to the last four favourite works of 2016. This one from a few years ago, Too Loud A Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal. A few blogs featuring this work recently and a feature film about to be released. Here’s what I wrote back in June:

Down to the last four favourite works of 2016. This one from a few years ago, Too Loud A Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal. A few blogs featuring this work recently and a feature film about to be released. Here’s what I wrote back in June: