‘The Mermaid of Black Conch’ has a very interesting back story, one I think is worthwhile sharing here, before I look at the book itself. Firstly the book was crowdfunded back in September 2019 to get into print, with an acknowledgement page appearing at the back of the book thanking the people who funded “this book out into the world.” Since then it has received rave reviews in the mainstream media and has appeared quickly on three respected Prize lists.

Prizes

In October 2020, the novel was shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize, and Award established by the University of London, “to celebrate the qualities of creative daring associated with the University and to reward fiction that breaks the mould or extends the possibilities of the novel form. The annual prize of £10,000 is awarded to a book that is deemed genuinely novel and which embodies the spirit of invention that characterises the genre at its best.” It didn’t win the Prize, losing out to ‘The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again’ by M. John Harrison.

In November 2020 the novel was shortlisted for the Costa Book Awards, an award for the most enjoyable books of the year by writers resident in the UK and Ireland” and last month it was named winner of the 2020 Costa Book of the Year.

Then in February 2021 the book was longlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize, an Award to celebrate “small presses producing brilliant and brave literary fiction” in the UK and Ireland. Small presses being defined as having fewer than five full-time employees.

A flurry of Award announcements and interestingly deemed not “daring” enough for the Goldsmiths but “enjoyable” enough to win the Costa.

The Publisher

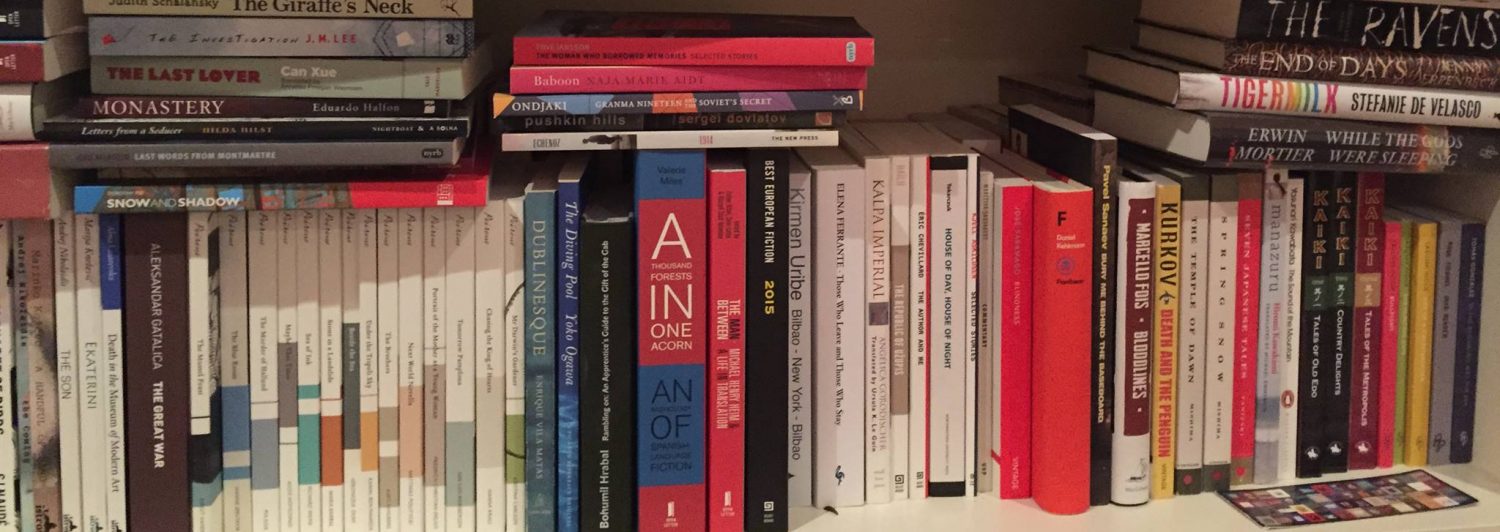

As the longlisting for the Republic of Consciousness Prize attests, this novel is published by a small press, less than five full time employees. Peepal Tree books “a small publisher that has consistently supported international Caribbean writing for 35 years.” Two days after the Costa announcement the press had sold 12,000 copies, having to move to a different printer to cope with demand.

There is an interesting article, and interview with founder and managing editor Jeremy Poynting available at ‘The Bookseller’ where he speaks of their list of 450 titles still being available, how ‘The Mermaid of Black Conch’ was crowdfunded to even get printed and the demands of a small publisher having a best-selling title in their catalogue.

The novel

We were both lost people.

David Baptiste is a fisherman in the small Caribbean enclave of Black Conch, one day whilst smoking a spliff and strumming his guitar on his boat, he spots a mermaid, Aycayia. A young girl who has been cursed for her beauty and temptation of men and sealed up with a tail and forced to swim the oceans for eternity. During a big game fishing competition she is caught by “those white men from Florida”.

This novel is told in a variety of voices, excerpts from David’s journal, short innocent lyrical poem like musings from Aycayia and the omniscient narrator, using local language and slang:

The Black Conch men, Nicholas and Short Leg, backed away from the stern. Like Nicer, they knew this was wrong. They fraid bad jumbie get ketch. They didn’t want to help. They were lost for words and for what to do. The white men wanted to pull this creature out of the sea. But this fish was half-woman, plain enough. Everyone had heard of the mermen in Black Conch waters, but a merwoman? No. She carried with her bad luck, at best, and her hair had frightened them – like she could kill you with just one lash from those tentacles. She could poison them all. They’d seen spikes on her back, dorsal spikes. Scorpion fish spikes, They had seen a bloody, raging woman on the end of the fishing line and now these white men wanted to bring her in. Nah, boy, they all said to themselves.

More than a simple love story, although the cover does say “a love story”, this is a complex study revealing misogyny, sex, the colonization and maltreatment of indigenous peoples, the destruction of the environment, modern day man’s move away from spiritual connection to their environment and the USA’s domination of the Caribbean amongst many subjects, all wrapped up in a tale of David Baptiste and Aycayia’s love.

The locals see the catch of a mermaid as potential bad luck, the Florida fishermen see the potential financial rewards. David sees his friend from the ocean, all strung up like a trophy catch and has to release her:

The old man, Thomas Clayson, had spent a second day at sea. He’d taken a rifle with him, this time, and some marine flares in case they got into trouble, also an axe and a cutlass as back up to the gun. He would shoot her if need bel that would be the end of it. He’d shot big game before. He’d shot a lion in South Africa, once. The head had been stuffed and mounted and was now above his desk in his den at home. He’d shot a buffalo in the Yukon, a female too; he’d even shot a grizzly bear, once, up in the Rockies. He would shoot the bitch, no messing, bring her in. No beers on the jetty; he’d take her straight, by truck, to the other end of the island, to the port at English Town, where she would be tagged and photographed and packed on ice and taken to the larger island/ There, she would be airlifted back to Florida. This time, he knew what he was up against; a big, bad motherfucker of a mermaid. He paid his crew double. He was furious over the theft of his catch, with the incompetence of the villagers, and mostly with his weak-minded sissy of a son.

There are interlocking love stories, abandoned single mothers, deaf children with connections to the environment and weird happenings, such as the skies raining fish, a wonderful blend of folklore, romance, and a race against time. Aycayia’s short melodic interludes dragging you back to simpler times:

I swam away, the dive deep

My terror was ENORMOUS

I swam but I still ketch

I want to go down to die

Enough shame put on my head

I was a human woman once

some thousand cycles past

Cursed to be lonely

with no love

They curse me good

Goddess Jagua was the goddess of their curse

She keep me lonely all those years

I miss my life in Black Conch

I was human woman again

after they ketch me good

There is also the underlying uneasiness of a “home”, is the mermaid’s home back on land from where she was banished, is it the sea? Are David’s roots in Black Conch? Is the white overseer’s place Black Conch? This pervading sense of displacement.

Baptiste is plantation owner name, French man name from way back. Yuh think I happy with that? I figure my real name would never be known to me, a mystery.

A wonderful blend of readability and prescience, a blend of tragic love story, environmental warning, folklore, with the pace of a thriller. A worthy winner of the Costa Prize and it is magnificent to see a novel that had crowdfunding beginnings, find a small publisher and then find success.