The Catalan “Ulysses”?

In recent months I have come across a plethora of references to James Joyce’s novel, with comparisons to numerous world literature works, must be the circles I mix in on social media! As frequent visitors here would know, I have recently reviewed part of Oğuz Atay’s “Tutunamayanlar” (“The Disconnecte d”), referred to as the Turkish “Ulysses” and today I look at Luis Goytisolo’s “Antagony”, more precisely “Recounting: Book 1”.

Here’s a few snippets of other reviewer’s thoughts, one taken from the publisher’s foreign rights page, the other from a site I visit often to explore world literature.

In whatever way, like Joyce’s Ulysses or Proust’s In search of lost time, like many others—or few others—you shouldn’t die without having read it (Antonio Martínez Asensio, blog Tiempo de silencio, Antena3.com)

In Spain, it is considered as one of the great works of 20th century literature, compared both to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time; Remembrance of Things Past). The comparison are certainly valid. Like the Joyce it is a Bildungsroman while, like the Proust, it is a long exploration of the artistic development of a young man. From the site “The Modern Novel” (although a great review it should come with a spoiler warning)

And then we have Mario Vargas Llosa (thanks to The Untranslated for this snippet ):

Besides being an ambitious and complex book, difficult to read due to the protoplasmic configuration of the narrative matter, it is also an experiment intended to renew the content and the form of the traditional novel, following the example of those paradigms which revolutionalised the genre of the novel or at least tried to do so — above all Proust and Joyce, but, also James, Broch and Pavese –, without renouncing a certain moral and civic commitment to historical reality which, although very diluted, is always present, sometimes on the front stage, sometimes as the novel’s backdrop.

Structurally this book does have a Proustian bent, following the life of Raúl Ferrer Gamide, a middle class Catalan, from childhood through army service, law studies, romantic interludes but more importantly his desire to be a writer. All against the political backdrop of Barcelona. I won’t be putting any spoilers in my thoughts here, rest assured if you decide to tackle this massive book I’ll allow you to discover the narrative yourself.

However, it is not the plot that is the main attraction here, it is the novel’s structure, grand sweeping exploration of Catalan society after the Spanish Civil War and the political luminosity that drags you along, through 648 pages.

A difficult book to read, we have ten page paragraphs, generally consisting of a single sentence, dialogue that forms part of the main text, so it is a challenge to understand who is speaking, a cast of hundreds, all with nicknames, some with code names and then broad philosophical debates, including political manifestos.

For example there are three page explanations as to why a door was locked at 3pm precisely, another three pages observing the eating of a ham sandwich, but it is the microscopic examination of Barcelona and the middle class that brings the richness to this novel.

A wonderful example of the craft is the beginning of Chapter IV, where the paragraph opens with “Coming down to Las Ramblas…”, an area of Barcelona, and ends with “their fitful procession heading up Las Ramblas.” In between there are descriptions of all the alleys, the crowds, the flowers, “confusing alleys and side streets with their little dives which stank of hashish, alleys where, as it grew dark, the shining lights isolated the ground floor businesses, the red doorways, the worn, narrow pavement, the filthy paving stones, high-heeled shoes, bulging hips, necklines, long manes of hair, painted eyes, a succession of bars, of turf marked off and intensified by cigarette smoke.”

Each of the players circle in and out of focus, and as we move through Raúl’s maturation from childhood to schooling, to army service, to his involvement with the socialist/communist party, his distribution of clandestine pamphlets, his legal work and dreams of being a writer, we learn more and more about Catalan society.

Classic references to things such as the “caganer”, the defecating figurine in Catalan nativity scenes, blend with discussions on Catalan poetry, literature, its demise and subsequent rise, and further discussions on Spanish speaking Catalonians, this is a detailed expose of cultural life.

In one section we have many pages describing the Sagrada Familia, Raúl simply walking in there to hide from the police, when suddenly the text lapses into descriptive explanations of the iconic Church:

And to the right, the Portico of Faith, enraptured altarpiece centred on the presentation of Jesus in the temple, with an outline of images now solemn and impassive, now violent, like the one of John the Baptist preaching in the desert, foretelling the coming of the Messiah, all that upon an embroidered background of wretchedness and suffering, of an interwoven framework of thorns and flowers, buds, corollas, thalamus, sepals, petals. Stigmata, honeybees drawn to pollen, and superimposed on the bramble-crag crenellations, the lantern, a three-peaked oil lamp, eternal triangle, base of Immaculate Conception, dogmatic effigy rising in ecstasy, like an ejaculatory prayer from within a large cascade of sprigs and grape clusters, all those details one can spot carefully from any one of the points of the belfry towers, as you climb the airy spiral staircases, from the doorways, from the enclosed balconies sinuously integrated on the projections of architraves and cornices of the frontispiece, balconies with bulbous wrought iron railings, small contoured galleries, catwalks, small steps, intestinal cavities, twisted corridors of irregular relief, passages conjoined in a coming and going from the belfries to the façade, four intercommunicating bell towers, harmonically erect. Which, if near their bases appear rather strangely compounded with the parameters of the porticoes, as the separate, each acquiring its own shape, they becomes curving parabolic cones, the two outer pairs equal in height, the two center towers taller.

The more you read of this complex work, the more you realise it is an homage to Barcelona.

Richly packed with snippets of historical data, with references to cultural icons and other books, there are also brilliantly referenced cultural scraps, for example when one character’s father suspiciously dies and the subsequent legal action over his business interests hots up, there is a reference to Goya’s “Trágala, perro”, “depicting some raving monks with a giant syringe about to forcibly administer an enema to a trembling man in the presence of his veiled wife.”

Suddenly an obscure etching has made itself into my sphere, and now my consciousness.

We also have a number of references to Marcel Proust, one of my favourite sections talking about a literary endeavour:

…we have a good example of that in Manolo Maragas, with his remembrances and reflections, with the magnified profiles of his memory, when he talks about Alicia and Sunche, when he talks about Magdalena’s grandmother as if she were the Duchess of Guermantes and as if Grandpa Augusto were the duke, and Doña America were Madame Verduin, and that crazy Tito Coll a sort of Charlus, while he, Manolo Moragas, the narrative I, an apathetic Marcel, too sceptical to take the trouble to write anything, the only reason for him not already having withdrawn into his cork-lined cell, becomes a chronicler of Barcelonan society, the literary transcription of whose avatars, for any reader not directly implicated in that world, would awaken the same interest, probably, as the prose of one of those stylists in the Sunday edition of a provincial newspaper who’ve achieved a certain notoriety by the agreeable character of the collaborations, stylists who philosophize like a sheep chewing its cud before the ruins of the Parthenon, not in service of the validity of the ideas developed, but rather, to please his readers’ palates, of the originality of the focus and the graceful exposition, as well as this stylist’s prose, the interest of the specific problems of that world, of the characters capable of inhabiting it, grazing and watering among the ruins of the culture, with the grace and subtlety and elegance of a bull’s head that, like Narcissus, gazes at itself in a puddle.

In a few lines, the depth of characters take on a new meaning, readers of Proust suddenly having another layer to the already complex players. But we are not restricted to Proust, the is a whole section questioning scholars and them not giving enough time to Dante’s Canto 34 in Inferno. Through drunken debates, scholarly discussions, a whole playing field of the author’s views can be spread on this massive canvas.

I must admit, there were many political sections where I tired of the proletariat debate, the roles of the bourgeois, the eternal struggle of the worker, however these political rants were more than adequately balanced with crystal clear observations of daily life, of the existentialist struggle. A Menippean satire? Possibly. A Catalan “Ulysses”, less likely, for a start it isn’t a single day…

A massively complex but thoroughly engaging work, unfortunately we have to wait until August 2018 for Book II to be released in English, and by that time it may mean a re-reading of “Recounting” is required, a novel that would reveal so much more upon every re-read, and so little time!!!

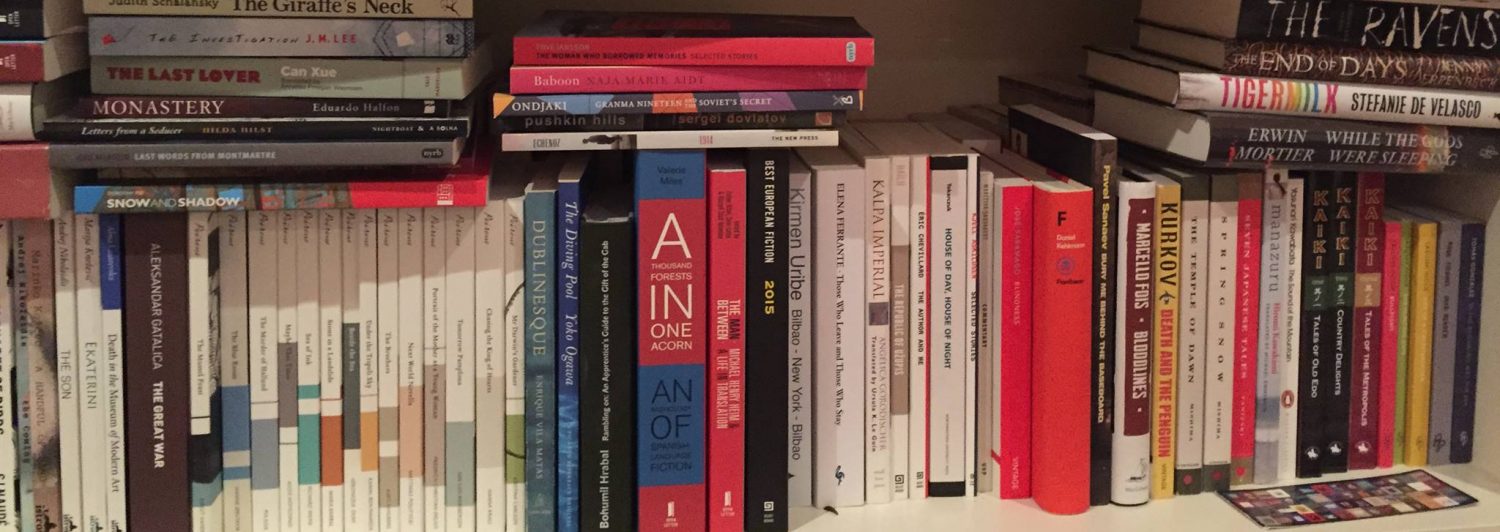

I am hoping to get to a few other world literature “Ulysses” over the coming months, I may tire of that journey but a few books I do have set aside are:

“Leg Over Leg” by Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq (all four volumes)

“Three Trapped Tigers” by Guillermo Cabrera Infante

“Adam Buenosayres: A Critical Edition” by Leopoldo Marechal

“All About H. Hatterr” by G.V. Desani

“Berlin Alexanderplatz” by Alfred Döblin

And of course I need to post my thoughts on the remaining section of Oğuz Atay’s “The Disconnecte d”

I am sure there are many many more books that fall into the “Ulysses” category, hopefully I get to discover their riches over the coming years.