The Argentine Ulysses?

In “Finnegan’s Wake”, James Joyce describes “Ulysses” as “his usylessly unreadable Blue Book of Eccles”, Leopoldo Marechal’s hero, Adam Buenosayres, has a notebook, which is presented in Book Six of this monolith, called “The Blue-Bound Notebook”. However, “Adam Buenosayres” (originally titled “Adán Buenosayres”) is not uselessly unreadable, in fact it is a very complex, many layered work, and it is not simply a “blue book” reference which links this work to “Ulysses”.

As regular visitors to this blog would know, I am, very slowly, looking at the many worlds of Ulysses and books that have been identified as being the “Ulysses” of their nation. Joshua Cohen identified “Adam Buenosayres” as the Argentine Ulysses, and unlike a few other works I have read the parallels here are justified.

The novel is expertly translated by Norman Cheadle (assisted by Shiela Ethier, who is credited on the title page but nowhere else!). Cheadle writes a detailed Introduction and provides 77 pages of detailed notes and a Bibliography, these are extremely handy to decipher a number of Argentine terms or references, and if the comparison to Joyce is considered tenuous then that should be dismissed quickly as the introduction provides a section titled “The Joyce connection and the culture wars”;

Another clear source of inspiration is Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) (p xiii)

This massive novel consists of seven “Books” and an “Indispensable Prologue”, where we learn, on the first page, that the protagonist is dead, after the funeral, Leopoldo Marechal advises us;

In the days that followed, I read two manuscripts that Adam Buenosayres had entrusted to me at his death: The Blue-Bound Notebook and Journey to the Dark City of Cacodelphia. Both works struck me as so extraordinary that I resolved to have them published, confident that they would find a place of honour in Argentine literature. But I later realized those strange pages would not be fully understood by the public without some account of who their author and protagonist was, so I took it upon myself to sketch out a likeness of Adam Buenosayres. At first I had in mind a simple portrait, but then it occurred to me to show my friend in the flow of his life. The more I recalled his extraordinary character, the epic figures cut by his companions, and above all the memorable exploits I had witnessed back in those days, the more novelistic possibilities expanded before my mind’s eye. I decided on a plan of five books, in which I would present my Adam Buenosayres from the moment of his metaphysical awakening at number 303 Monte Egmont Street until midnight on the following day, when angels and demons fought over his soul in Villa Crespo, in front of the Church of San Bernardo, before the still figure of Christ with the Broken Hand. Then I would transcribe The Blue-Bound Notebook and Journey to the Dark City of Cacodelphia as the sixth and seventh books of my tale. (pp3-4)

Like Joyce’s “Ulysses”, which focuses on a single day in Dublin, these first five “books” of “Adam Buenosayres” focuses on three days, April 28-30, in an unspecified year in the 1920’s, in Buenos Aires (hence the protagonist’s name). It does say “one day” in the introduction however we also have the manuscripts themselves and, of course, the funeral. But I could rant on for ages about the influences and inspirations, the translator’s introduction to the book most definitely explains it better than I ever could.

As explained by Norman Cheadle, this work could be interpreted as a Roman à Clef, a novel with real life keys overlaid with a façade of fiction. The main characters “carticatures of clearly recognizable individuals”, Luis Pereda is Jorge Luis Borges, the astrologer Schultz being the artist Xul Solar, the philosopher Samuel Tesler is the poet Jacobo Fijman, and Bernini the writer Raúl Scalabrini Ortiz, the protagonist Adam Buenosayres Marechal himself. Buenosayres’ beloved, Solveig Amundsen has been associated with Norah Lange, however this is under dispute. Cheadle says “caution must be exercised when interpreting Adán as a roman à clef. On the other hand, it can be read as a Kűnstlerroman whose most obvious model is Joyce’s Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, though these two subgenres can hardly account for the novel in its totality.”

A work so rich in literary styles it requires a serious commitment if you want to enjoy its riches, it is a book that demands many readings, and the rewards for complete immersion and further study would obviously be many, however Norman Cheadle greatly assists any reading with his detailed notes.

He haunted the night because, in his era, the torch of daytime incited a war without laurels; it raped silence, it scourged holy stillness. Daytime was external like skin, active like the hand, sweaty as armpits, loud-mouthed and prolific in falsehood. Male by sex, daytime was a young hairy-chested hero. He shied away from the light of day because it pushed him toward the temptation of material fortune, induced the anxiety to possess useless objects, as well as other unhealthy desires: to be a politician, boxer, singer, or gunman. “and the night?” Colourless, odourless, insipid as water, nighttime nevertheless kindled the dawn of difficult voices and deep calls which the day with its trombones drowns out. Antipode of light, night made the tiny stars visible. Destroyer of prisons, she favoured escape. Field of truce, she facilitated union and reconciliation. Female who healed, refreshed and stimulated, she lay with man and conceived a son called sleep, the gracious image of death. (pp19-20)

The story of a man, struggling with unrequited love, a hero who is about to undertake adventures, where the underbelly of Buenos Aires will be exposed. The first five books, consisting of 355 large pages, is Marechal coming to terms with his place in Argentina, his struggles with writing and his role within the wider literary circle;

Did Adam concoct, as was his wont, some poetic analogy to express such a vexed duality? He had no need, Plato’s inimitable simile sprang to mind: his soul was a like a wingèd chariot pulled by two different horses. One of them, sky-coloured, its mane bristling with stars, its delicate hooves airborne, tended to draw always upward, toward the heavenly meadows where it was born. The other, earth-coloured, slack-lipped, balky, its crupper twisted, paunchy, long-eared, knock-kneed, down at the mouth, and stumble-gaited, always pulled downward, itching to get stuck in muck up to the crotch. Poor Adam, the driver, held the reins of both horses and strove to keep them on track. When the accursed colt prevailed and dragged down the soul’s entire equipage, the divine equine seems to be asleep in its traces. But when the celestial steed took over, its limbs plied a marvellous light, its nostrils flared to the scent of divine alfalfa fields, and the coach flew, hoisting aloft the dead weight of the earthly horse. The sublime charger kept going higher until it sensed the air thinning, its sinews slackened, and it fell asleep drunk on loftiness. That’s when the terrestrial animal woke up and, finding its teammate asleep, let itself fall down hard, given over to voracious hunger for impure matter. When satiated, this beast nodded off, the noble bronco awoke and was master of the coach once more. Thus, between one horse and the other, between heaven and earth, now pulling on this rein and now on that one, Adam’s soul rose up or tumbled down. At the end of each trip Adam the coachman wiped acrid sweat from his brow. (p27)

Using many literary and philosophical references throughout, the influences of European thinking and culture upon Argentine progress is a subtle backdrop to the travails of our hero and his merry band of writers, artists, poets. The philosopher Samuel Tesler appears in chapter two, he does not wash as a rejection of being baptised (as per Stephen Dedalus?) and his appearance ensures there are many philosophical debates throughout their journey.

In Book Two, Adam Buenosayres wanders the streets, a la Bloom in “Ulysses” and meets a large cast of characters, this is the melting pot of Buenos Aires. A funeral crosses his path, we have dishwashers calling on Melpomene “the tragic muse” quoting poetry, Polyphemus appears as a blind street beggar who owns rental properties, drinking funeral coachmen, old witches who have been fleeced, men doffing hats to statues of Christ, large pregnant women, nymphs in blue, white and green revealing a “Hesperides of incalculable abundance”, Clotho with a spinning wheel, Syrians smoking the narghile, and it all comes together with a resounding crescendo…a fight;

Standing in the first row of the ring, Adam Buenosayres studied the combatants. There were the Iberians of thick eyebrows who’d left northern Spain and their dedication to Ceres to come here and drive orchestral streetcars; there were those who drank from the torrential Miño River, men practiced in the art of argumentation; those from the Basque countries, the natural hardness of their heads concealed by blue berets. Then there were the Andalusian matadors, abundant in guitars and brawls. And industrious Ligurians, give to wine and song. Neopolitans erudite in the fruits of Pomona, who now wield municipal brooms. Turks of pitch-black mustachios, who sell soap, perfumed water, and combs destined for cruel uses. Jews wrapped in multi-coloured blankets, who love not Bellona. Greeks astute in the stratagems of Mercury. Dalmatians of well-rivetted kidneys. The Syrio-Lebanese, who flee not the skirmishes of Theology. And Japanese dry-cleaners. In short, all those who had come from the ends of the earth to fulfil the lofty destiny of the Land-which-from-a-noble-metal-takes-its-name. Adam studied those unlikely faces and wondered about that destiny, and great was his doubt. (p94)

As the journey continues the reader is exposed to an array of Argentine history, myth and sub-cultures, the five books coming to a nationalistic conclusion;

The Argentine, by nature, was and must be a sober man, as our country folk were and still are. And so were, and are, the immigrants responsible for the existence of the majority of us. Bet what’s happened? Foreigners have induced us into a cult of sensuality and hedonism, inventing a thousand needs we didn’t have before. And – of course! – it’s all so they can sell us the geegaws they produce industrially, and so redeem the gold they pay us for our raw materials. In plain language, that’s what I call eating with both hands! (p336)

A full novel contained in the first five books, Marechal’s “Ulysses”, but this only constitutes a little over half of the work, we still have “The Blue-Bound Notebook” and the final book “Journey to the Dark City of Cacodelphia”.

“The Blue-Bound Notebook” is a metaphysical exploration, a delving into the soul of Adam Buenosayres, a philosophical musing on existence and love. The book where he has written his inner most desires for Solveig, this section explores Adam’s heart;

She moved slowly forward, beneath a sun perpendicular to the earth: her body, without shadow, had the firm fragility of a branch, a sort of combative force in her lightness, a terrible audacity in her decorum. She wore a sky-blue dress wrapped round her like a whisp of mist; but the garden, the light, the air, all heaven and earth joined forces and worked to clothe her, so much to be feared was her nakedness. With her face turned to the sun, she showed the two violets of her eyes and the slight arc of her smile; a bee buzzed in circles around her hair. As she walked, her small feet crushed golden sand, seashells, and the carapaces of blue beetles. Her arrival seemed to last an eternity, as it The One came from very far off, across a hundred days and a hundred nights. (p384)

After exploring Adam Buenosayres soul and inner machinations it is time for a decent into Hell, a la Dante’s “Inferno”, here nine stages of the helicoid tracking the living hell of Buenos Aires, the masses chewing, swallowing and shitting whatever news is fed to them, sexual debauchery, where Chapter 15 “Circe” in “Ulysses” instantly sprang to mind;

Why, it’s Don Moses Rosenbaum! He has exhumed his ancient lustring frock coat and his astrakhan hat. See how his crazed gaze wanders over the banquet table! And observe how, in the face of such devastation, he tears tufts from his beard, weeps without a sound, raises his arms toward the ceiling, as though trying to prop it up? Great God, what’s he doing now? In his madness, the poor wretch has started gathering crumbs from the tablecloth, righting toppled glasses, and salvaging the spilled wine. But no one sees or hears him, and around him the debauchery intensifies. (p470)

Occasional spices of humour appear, for example the dragon guarding the door into the fifth circle of hell needs to be put to sleep, how they do so is to read it Argentine literature.

A massive novel that contains riches upon riches, a work that deserves better recognition as a canonical piece of Argentine literary history, a book that is not an easy read, a mental exercise that took me many months to complete. Late in the book Leopoldo Marechal explains it thus;

Reader, my dear friend, if I had to justify the drowsiness that came over me in the fourth circle of Schultz’s inferno, I should remind you of a hundred illustrious precedents recorded in as many infernal excursions. Alighieri, being who he was, slept quite a bit in the descent he made. If the metaphysical character of his journey allows us to assign a symbolic value to that bard’s siestas, we can say that Alighieri slept in the proper place at the proper time. Less fortunate than he, I made an infernal descent without theological projections. I didn’t sleep when I should have, but rather when it was humanely possible to do so. How lucky are you, reader! For, having no metaphysical obligations or any cares whatsoever, you can cop a snooze on any page at all of this, my true story! (p481)

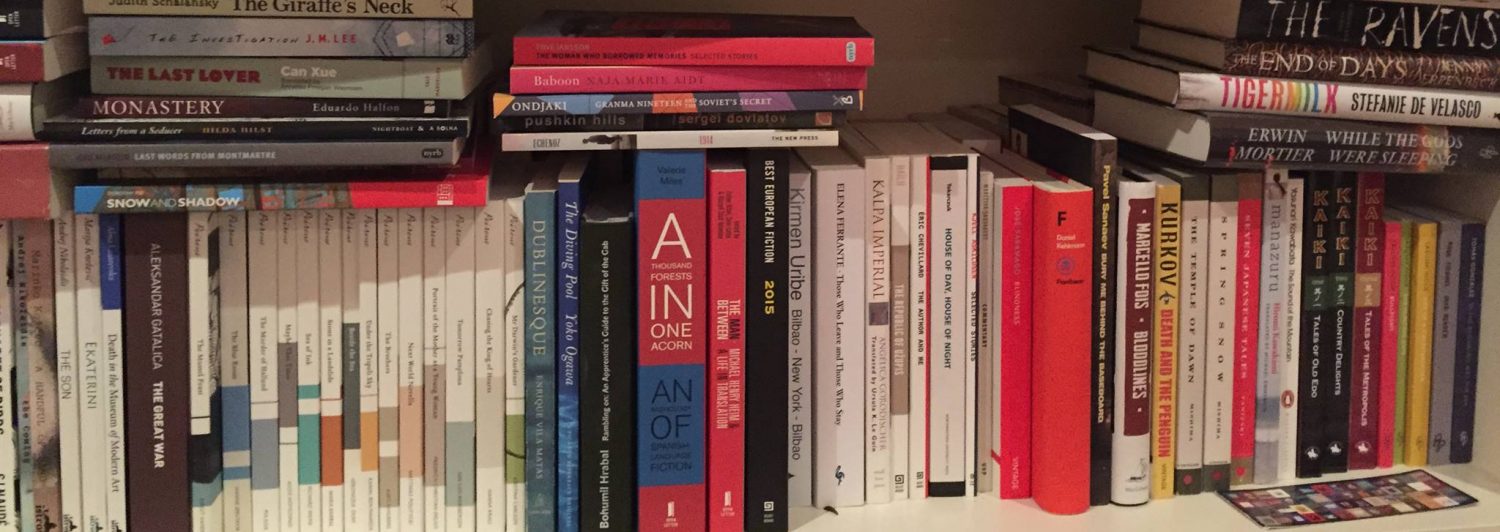

Underappreciated, sadly released in English with barely a whimper, “Adam Buenosayres” was longlisted for the 2015 Best Translated Book Award, not even making the shortlist (the eventual winner was Can Xue’s “The Last Lover”), which is extremely disappointing given the massive effort that the translator has put in here and given the novel’s place in Argentine literary history. Lauded by Julio Cortázar shortly after the novel was released in 1948, where he said “The publication of this book is an extraordinary event in Argentine literature.”

For lovers of complex literature this is worth reading, not because it is a materwork, but just for the ending where an insatiable desire of knowledge and the allure of reading is debated. Of all the national “Ulysses” I have read, I must say the comparison here is completely justified.

Thanks for this fascinating and illuminating account of a book I didn’t know. It’s so long since I read Ulysses I’d feel the need to go back to it – will certainly put this on the list.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ok. Maybe 3rd try will do it. I cant seem to get much beyond the apartment at the start. I recall w Gravities Rainbow something clicked about 75 pages in. Heres hoping for similar. Glad to hear it’s not just sadly derivstive.

LikeLiked by 1 person