In the early sections of Arno Schmidt’s “Bottom’s Dream”, which I am slowly making my way through, there are several references to Friedrich Heinrich Karl de la Motte, Baron Fouqué’s most popular work “Undine”. As part of my unravelling and immersion into Schmidt’s book, I purchased and read the novella from the German Romantic period. First published in 1811, the same year as Jane Austen’s “Sense and Sensibility” (originally titled “Elinor and Marianne”) and a year before the German brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm published their “Children’s and Household Tales”, “Undine” tells the tale of a watersprite, a nymph with the unique ability to assume the human form.

Following the well-worn Romantic theme of female characters being chaste, subservient, obedient, coquettish slaves, “Undine” tells of Sir Huldbrand of Ringstetten, a knight who lives in a castle near the source of the Danube. A chivalrous man who travels into a “very wild forest, which, both from its gloom and pathless solitude as well as from the wonderful creatures and illusions with which it was said to abound, was avoided by most people except in cases of necessity.” He does so on the wishes of a noble woman, Bertalda. In the forest he comes across a fisherman, his wife and their adopted daughter, Undine.

The knight interrupted the fisherman to draw his attention to a noise, as of a rushing flood of waters, which had caught his ear during the old man’s talk, and which now burst against the cottage-window with redoubled fury. Both sprang to the door. There they saw, by the light of the now risen moon, the book which issued from the wood, wildly overflowing its banks, and whirling away stones and branches of trees in its sweeping course. The storm, as if awakened by the tumult, burst forth from the mighty clouds which passed rapidly across the moon; the lake roared under the furious lashing of the wind; the trees of the little peninsula groaned from root to topmost bought, and bent, as if reeling, ober the surging waters. “Undine! For Heaven’s sake, Undine!” cried the two men in alarm. No answer was returned, and regardless of every other consideration, they ran out of the cottage, one in this direction, and the other in that, searching and calling.

As a young girl Undine had appeared at the fisherman’s door, to naturally replace their daughter who had fallen into the lake and disappeared. As a young girl Undine (who chose her own name to be used for christening) spoke of golden castles and crystal domes. Whilst both the nameless fisherman and his wife (who is a lightly sketched character) question Undine’s sanity they are not aware that she is in fact a water nymph who has taken human form. She lacks a soul, but can gain one by marrying a mortal – and conveniently for our tale the knight in shining armour, literally, rides into her world.

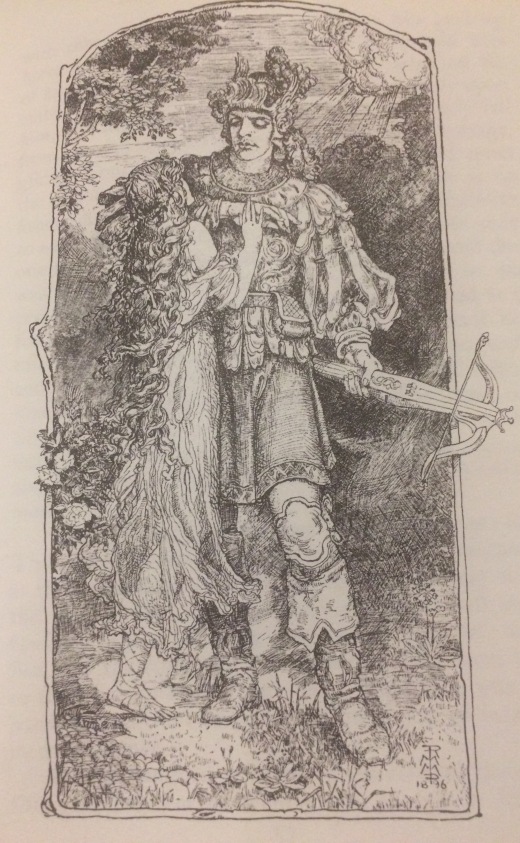

A mysterious tale with water, moisture references throughout, as Undine marries the knight and her evil uncle, who lives in creeks, fountains, lakes attempts to get Sir Huldbrand to “forsake” Undine near water so she will lose her human soul and return to life as a watersprite. Light romanticism with allusions to sexual activity, the illustrations are more risqué than the text itself, here is the opening paragraph from the chapter titled “The Day After The Wedding”:

The fresh light of the morning awoke the young married pair. Wonderful and horrible dreams had disturbed Huldbrand’s rest; he had been haunted by spectres, who, grinning at him by stealth, had tried to disguise themselves as beautiful women, and from beautiful women they all at once assumed the faces of dragons, and when he started up from these hideous visions, the moonlight shone pale and cold into the room; terrified he looked at Undine, who still lay in unaltered beauty and grace. Then he would press a light kiss upon her rosy lips, and would fall asleep again only to be awakened by new terrors. After he had reflected on all this, now he was fully awake, he reproached himself for any doubt that could have led him into error with regard to his beautiful wife. He begged her to forgive him for the injustice he had done her, but she only held out to him her fair hand, sighed deeply and remained silent. But a glance of exquisite fervour beamed from her eyes such as he had never seen before, carrying with it the full assurance that Undine bore him no ill-will. He then rose cheerfully and left her, to join his friends in the common apartment.

The fantasy fairy tale language a pleasure to read, bringing back childhood memories of similar tales (although I’m not sure I had tales like these to read, ageing memory getting me!!!) And reading this work with an Arno Schmidt bent made some of the references to “Crystal” (see an earlier “Bottom’s Dream” post about the etym there) did make me smile.

The fantasy fairy tale language a pleasure to read, bringing back childhood memories of similar tales (although I’m not sure I had tales like these to read, ageing memory getting me!!!) And reading this work with an Arno Schmidt bent made some of the references to “Crystal” (see an earlier “Bottom’s Dream” post about the etym there) did make me smile.

“You must know, my loved one, that there are beings in the elements which almost appear like mortals, and which rarely allow themselves to become visible to your race. Wonderful salamanders glitter and sport in the flames; lean and malicious gnomes dwell deep within the earth; spirits, belonging to the air, wander through the forests; and a vast family of water spirits live in the lakes and streams and brooks. In resounding domes of crystal, through which the sky looks in with its sun and stars, these latter spirits find their beautiful abode; lofty trees of coral with blue and crimson fruits gleam in their gardens; they wander over the pure sand of the sea, and among lovely variegated shells, and amid all exquisite treasures of the old world, which the present is no longer worthy to enjoy; all these the floods have covered with their secret veils of silver, and the noble monuments sparkle below, stately and solemn, and bedewed by the loving waters which allure from them many a beautiful moss-flower and entwining cluster of sea-grass. Those, however, who dwell there, are very fair and lovely to behold, and for the most part, are more beautiful than human beings. Many a fisherman has been so fortunate as to surprise some tender mermaid, as she rose above the waters and sang. He would then tell afar of her beauty, and such wonderful beings have been given the name of Undines. You, however, are now actually beholding an Undine.”

As Sir Huldbrand learns of Undine’s background and they travel back through the haunted forest to advise Bertalda that no harm has befallen the hero, the story turns into a romantic love triangle, as we know Sir Huldbrand cannot forsake Undine (she is totally in his power) near water or she will lose her soul and Bertalda had romantic feelings for the knight prior to his departure and the interruptions by Undine’s uncle Kühleborn we know this tale is not going to end happily.

But in a region, otherwise so pleasant, and in the enjoyment of which they had promised themselves the purest delight, the ungovernable Kühleborn began, undisguisedly, to exhibit his power of interference. This was indeed manifested in mere teasing tricks, for Undine often rebuked the agitated waves, or the contrary winds, and then the violence of the enemy would be immediately humbled; but again the attacks would be renewed, and again Undine’s reproofs would become necessary, so that the pleasure of the little party was completely destroyed. The boatmen too were continually whispering to each other in dismay, and looking with distrust at the three strangers, whose servants even began more and more to forebode something uncomfortable, and to watch their superiors with suspicious glances. Huldbrand often said to himself: “This comes from like not being linked with like, from a man uniting himself with a mermaid!” Excusing himself as we all love to do, he would often think indeed as he said this: “I did not really know that she was a sea-maiden, mine is misfortune, that every step I take is disturbed and haunted by wild caprices of her race, but mine is not the fault.”

Throughout the male hero does not take responsibility for his actions, falling for a stunningly beautiful woman, asking her to marry, taking her to a new home, sharing his love with another woman and “mine is not the fault”!!! An interesting tale with the forlorn swooning woman falling for the knight, gaining a soul, holding control through the evil spirit intervention, however wanting to keep her human soul, she is wholly dependent upon the male lead, she is his subservient, obedient, coquettish slave. Often falling into tears to manipulate the hero on horseback the water nymph never takes control of her fate, knowing she is trapped by the curse that the male can forsake her at any time.

This chivalrous tale has an interesting ending (which I will not give away) and one that is a little more pleasant than the ending of the Grimm Brother’s tale “Mother Trudy” – a tale I read as it was referenced Clemens Meyer’s “Bricks and Mortar” (translated by Katy Derbyshire), a recent translated release. The Grimm tale ending as follows:

And with that, she turned the girl into a block of wood and threw it on the fire. And when it was blazing, she sat down beside it, warmed herself up, and said: “Now that really does give off a nice bright light.”

The edition of “Undine” I purchased is published by Dedalus European Classics and interestingly a translator is not credited, the introduction telling us “in 1897 alone, two new translations were published, of which the present is one.” A tale that brings the innocence of nature to life through a character and the suffering that is humanity befalling her as she gains a soul, Undine moving from innocence to sorrow simply through marriage, or through gaining a human soul.

A worthwhile transgression from the reading of “Bottom’s Dream” and I am sure there will be many more references in Schmidt’s novel that I will come across in my journey…..back to it.

Hi, liked this article and the information, I had come across Undine as a central theme in Monique Scwitter’s shortlisted book Eins im Andern which I posted last year and had thus read descriptions of but not Motte Fouqué’s work.

Pat

LikeLike

Pingback: German Literature Month VI: (Belated) Author Index | Lizzy's Literary Life