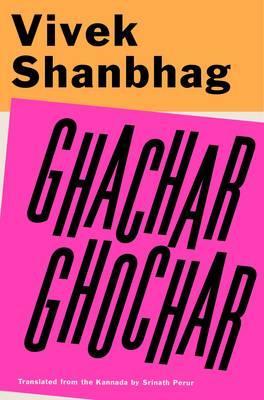

My second post in my series “Why xxx can not win the Best Translated Book Award”. Today I look at “Ghachar Ghochar” by Vivek Shanbhag (Translated from the Kannada by Srinath Perur).

Let’s state the obvious (might have to be a standard opening line for this series!), the Best Translated Book Award is for the small independent publishers to highlight their wares. The publishers that have taken home the fiction award to date have been Soft Skull, Archipelago, Melville House, New York Review of Books, New Directions, Yale University Press, And Other Stories and Open Letter, “Ghachar Ghochar” is published by Penguin, yes there’s been a big one before but c’mon Penguin stop raining on somebody else’s party!!!

When I pick up a book from India, I expect a caste struggle or a historical fiction, moving from colonial rule to independence. Rohinton Mistry gave us the untouchable leather workers Ishvar and Omprakash, in “A Fine Balance”, Salman Rushdie a protagonist, Saleem, who was born at midnight on 15 August 1947, the exact moment India became and independent country. And I could cite example after example of what I expect when reading fiction from India. Here there’s not an untouchable in sight, and there is a small veiled reference to progress;

The walls are panelled in wood to shoulder height. Old photographs hang on the sturdy square pillars in the center of the room, showing you just how beautiful this city was a century ago. The photographs evoke a gentler, more leisurely time, and somehow Coffee House still manages to belong to that world. For instance, you can visit at seven in the evening when it’s busiest, order only a coffee and occupy a table for two hours, and no one will object. They seem to know that someone who simply sits there for so long must have a thousand wheels spinning in his head. And they know those spinning wheels will not let a person be. Eventually, he’ll be overwhelmed, just like the serene spaces in those photographs that buyers devoured and turned into the cluttered mess we have around us today. (pp1-2)

Here we have a novel where the unnamed narrator, protagonist has moved from a poor upbringing, a crowded home infested with ants, to living a life of relative luxury, a director who doesn’t have to work, a member of the middle class. This change in fortunes comes about through an uncle who has successfully set up a spice distribution business, the family who all live together have moved from struggling to bourgeois;

Our only fear now is he might lose his mind with age and become ruinously entangled in some philanthropic enterprise. So we try to keep him in a good mood, making sure he doesn’t lose his taste for food or develop other ascetic tendencies. We steer him clear of thoughts about the futility of life and so on. An unfortunate consequence of this is that we must endure his garrulity whenever he emerges from his shell – the same old stories, again and again. Who knows what pleasure he gains from reminding us of the days when we struggled to get by in this city on a tiny income. (pp23-24)

However the story is not simply about the rise from poverty to relative wellbeing, it begins in a coffee house with the narrator reflecting upon his life of luxury and reminiscing about the journey that led to him whiling away the hours sipping coffee, the main theme being family bonds, were times better when money had to be watched, when budgeting was required when a new pair of trousers were required;

Soon the house was crammed with expensive mismatched furniture and out-of-place decorations. A TV arrived. Beds and dressing tables took up space in the rooms. In retrospect, many of the new objects had no place in our daily lives. Our relationship with things we accumulated became casual; we began treating them carelessly. (p52)

I want a story like “Slumdog Millionaire”, you know the type, rise from depths, become successful, have your success cruelly taken away, these are the successful story lines that should be promoted, none of this “the biggest drama in my life is some unknown woman vying for the man of the house’s affections” rubbish. And what an incomprehensible title, you can’t give an award to a book you can’t pronounce!!!

The next morning, we woke up in a hopelessly rumpled bed. I entwined my legs in hers and said, “Look, we are ghachar ghochar now.” She did not laugh. She must have thought I was making fun of her. Of course, those words could never mean to me all that they meant to her; nor would I ever utter them as naturally as she did. But she had shared with me this secret phrase that didn’t exist in any language, and now I was one of only five people in the world who knew it. (p78)

A novella that is constructed with simple concise and familiar prose, believable well shaped characters, a tight knit family who is presided over by the male character who dragged them from the mire;

It’s true what they say – it’s not we who control money, it’s the money that controls us. When there’s only a little, it behaves meekly; when it grows, it becomes brash and has its way with us. Money had swept us up and flung us in the midst of a whirlwind. (p53)

Finally the other downfall is the length, this runs to a mere 118 pages, it is a book you can read in a single sitting. Where’s the knitted brow as you decipher philosophical existentialist angst, where grand literary themes are presented in a labyrinth of complexity? This is what I expect from translated fiction, an independent publisher exposing me to the cultural nuances of a region I know nothing about, not a comfy family drama of the middle class, well to do in India, what on earth are these judges thinking???

Ouch!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha

LikeLiked by 1 person

The curmudgeon’s guide to the BTBA? A fine backhanded compliment there. I just finished this book and found it so enjoyable but not certain it would be my choice to win.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If I put on my “non grumpy” hat, it is actually a pleasant book, but I’m with you on winning the award. There are others I’ve read that are well and truly in front.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: 2018 So Far – READER AT LARGE (formerly BookSexy Review)

At first I thought you were being sarcastic, particularly when I came across this: “When I pick up a book from India, I expect a caste struggle or a historical fiction, moving from colonial rule to independence… And I could cite example after example of what I expect when reading fiction from India. Here there’s not an untouchable in sight, and there is a small veiled reference to progress”

How terrible, I suppose, that somebody wrote a book with some semblance of authenticity, as opposed to gratifying the desires of non-Indians by churning out book after book on the exact topics you mentioned and nothing else.

And, yes—surprise!—people in India aren’t that dissimilar from people in Australia or Kenya or Peru. They’re just people. Sorry to disappoint you.

LikeLike

Thanks for stopping by – unfortunately you’ve no sense of humour. The series of posts are all sarcastic, yearly the Best Translated Book Award runs a series of why xxx should win, this piece is making fun of that series (as are the others eg. I don’t believe colouring books draw us closer to the devil).

This was written to highlight how too many people put blind assessments on books before reading them.

Unfortunately you’ve missed the point.

LikeLike